6 minutes

AI Adoption Starts with Internal Capability

AI adoption is often framed as a tooling problem or a skills problem. In practice, it’s usually neither.

Most organisations already have access to capable AI tools. Many already have people experimenting with them. What’s missing is internal capability—the ability for an organisation to use AI confidently in day‑to‑day work.

Leadership support and funding matter, but not as ends in themselves. They matter because they create the conditions for that capability to form.

Without it, AI remains optional. And optional things rarely change how work actually gets done.

When I talk about AI here, I’m mostly referring to large language models and the tools built around them. Not because other forms of AI don’t matter, but because LLMs are the first that meaningfully show up in everyday work for large parts of an organisation.

Adoption Starts Inside the Organisation, Not in the Product

One mistake I see repeatedly is organisations jumping straight to embedding AI into their products. The instinct is understandable. Product impact is visible. It’s easier to justify. It feels like progress. But it skips a critical step.

Before an organisation can responsibly ship AI‑powered features, it needs to become comfortable using AI in its own day‑to‑day work. Writing, planning, analysing, reviewing, questioning. The unglamorous internal workflows that never make it into a launch blog post.

That’s where intuition forms. That’s where people learn what AI is good at, where it hallucinates, how it fails, and how much oversight it really needs.

Without that lived experience, product‑level AI decisions are made in the abstract.

Executive Signals Matter More Than We Like to Admit

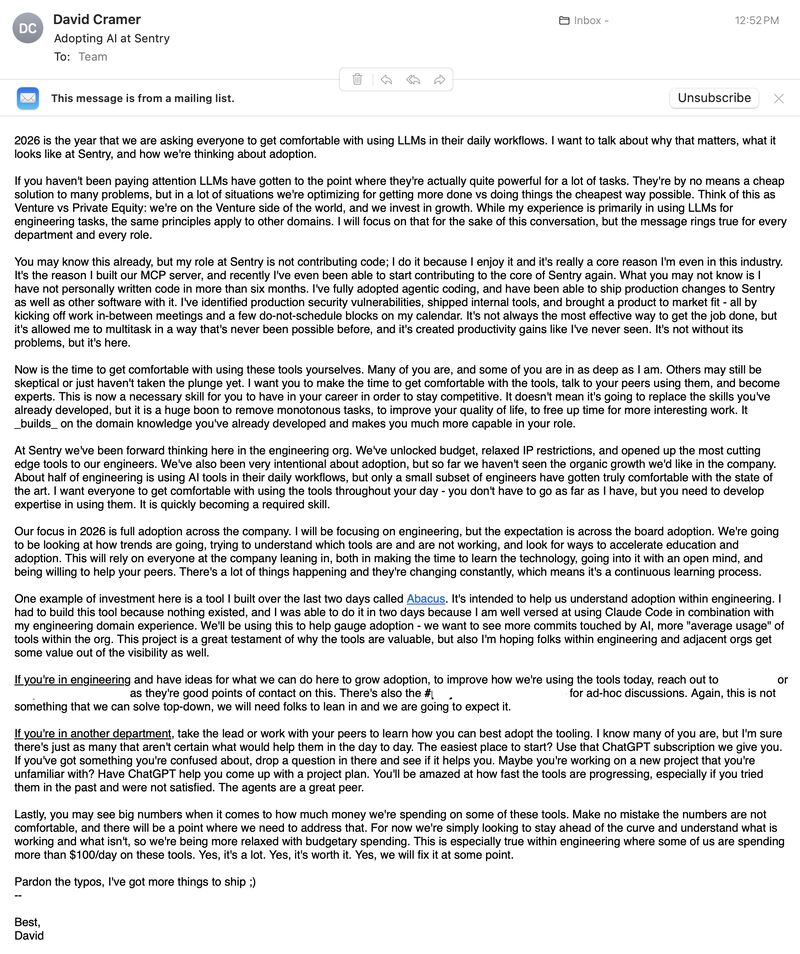

Recently, the CEO of Sentry shared a company‑wide note encouraging everyone—not just engineers—to become comfortable using LLMs in their daily work.

What stood out wasn’t enthusiasm for the technology itself, but the clarity of intent.

AI usage wasn’t positioned as a side experiment or a personal productivity trick. It was framed as something worth investing time in, with funding to support that learning and an explicit acceptance that the process would be imperfect.

Some people instinctively recoil at this kind of top‑down encouragement. I think that reaction misses the point.

In most organisations, the absence of a mandate is itself a signal. If leadership doesn’t clearly say “this matters,” people assume it doesn’t—at least not enough to justify the time it takes to learn something new.

You can’t ask people to change how they work and simultaneously make that change feel unofficial.

Grassroots Adoption Has a Ceiling

Organic adoption gets talked about a lot. A few curious people try new tools, share prompts, maybe give a short demo. That’s useful, but it doesn’t scale.

Learning to use AI well takes time—time to experiment, to produce mediocre output, to understand what works and what doesn’t. If that time isn’t explicitly protected, it competes directly with delivery pressure. Delivery almost always wins.

The result is predictable: a small group gets comfortable, most people opt out quietly, and leadership concludes that AI “didn’t really move the needle.”

Even the People Closest to AI Feel Behind

What’s interesting is that this isn’t just a problem for non‑technical roles.

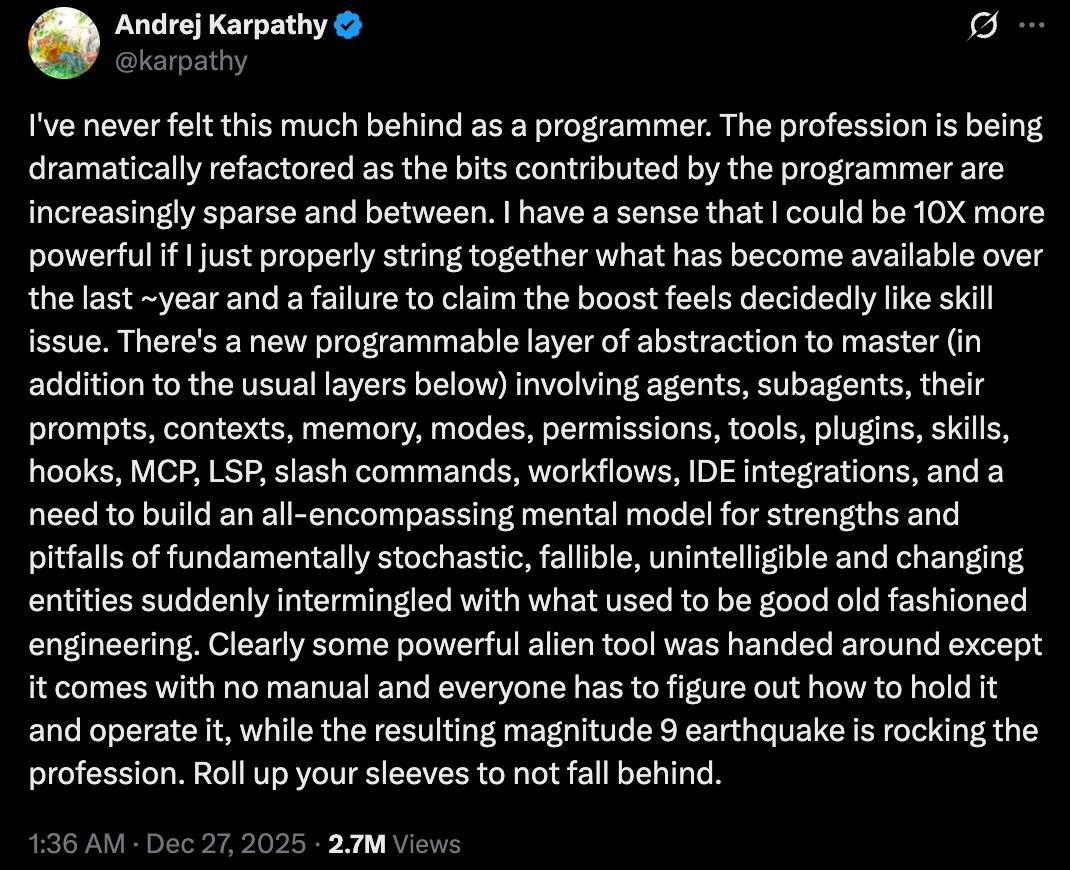

Andrej Karpathy recently shared that he feels behind as a programmer. If someone who has spent years at the sharp edge of AI feels this way, it shouldn’t be surprising that most organisations are struggling to keep up.

The bar is moving quickly. Expecting people to absorb that change in their spare time isn’t a serious strategy.

AI as a Thinking Partner

The framing matters as much as the tools.

The healthiest adoption I’ve seen treats AI as a thinking partner rather than a replacement. Something you use to sanity‑check assumptions, question whether you’re solving the right problem, or surface blind spots you didn’t notice.

That framing works best when AI is part of everyday work. Not a special tool you pull out for demos, but something you use often enough to develop judgment.

You don’t get that judgment from a roadmap. You get it from repetition.

A Virtuous Cycle of Capability

Internal capability is built through everyday use, safety, repetition, and learning. Over time, that creates a virtuous cycle.

It’s useful to think about AI in the same category as word processors or spreadsheets.

Most organisations already see a wide gap in how effectively different teams use those tools. Some use them at a basic level—enough to get by. Others have developed much deeper fluency and move faster as a result. The productivity difference between those groups is obvious, even though they’re using the same underlying software. AI will follow the same pattern.

The biggest gains won’t come from a small group doing impressive things with advanced techniques. They’ll come from lifting the baseline—getting everyone comfortable enough that AI becomes a normal part of how work gets done. That’s where the real organisational leverage is.

As people become more comfortable using these tools, they start to understand both their limits and their strengths. They learn where AI adds leverage, where it introduces risk, and where human judgment still matters most.

That understanding feeds back into better questions, better experiments, and ultimately better ideas. Product opportunities stop being speculative and start being informed by lived experience.

The organisation isn’t guessing what AI might be good for—it’s drawing on what it already knows.

Talking About AI Without Living It

One of the most common failure modes is a gap between what leadership says and how AI usage is received day to day.

On one hand, people are encouraged to “use AI more.” On the other, when AI‑assisted work introduces noise, rough edges, or imperfect output, it’s criticised or quietly dismissed.

The message that lands is simple: don’t take the risk.

A more forward‑thinking approach treats imperfect output as part of the learning curve. When someone uses AI poorly, that’s not a reason to discourage usage—it’s an opportunity to help them use it better.

You can’t demand experimentation while punishing the early results.

Funding Is How Leaders Make Capability Possible

This is where leadership funding matters most.

Funding AI adoption isn’t just about buying tools. It’s about paying for the time and safety needed for people to build intuition before those decisions become product‑critical.

Funding isn’t the goal. Capability is. Funding is how leaders make capability possible.

Once money is committed, priorities become clearer. People feel permission to invest in learning. Managers stop treating AI usage as a distraction.

Only then does it make sense to ask how AI should show up in the product.

A Necessary Caveat

The point here isn’t that organisations should never ship AI to customers early.

Some companies have learned quickly by deploying AI directly into customer‑facing workflows and iterating from there. That approach can work, especially when the risks are well understood and tightly managed.

The claim is narrower than that.

You don’t become good at AI by shipping it first. You become good at AI by living with it.

When people across the organisation understand AI’s strengths and pitfalls through daily use, the ideas that eventually make it into the product tend to be better, safer, and more grounded.

That foundation may feel slower at first. In practice, it usually accelerates everything that follows.

What Comes Next

This is the first in a series of posts on AI adoption.

Next, I’ll share how I’ve been using AI to improve my own workflow. In that post I hope to share where it adds little value, or where not using it is the better choice.

Understanding both sides is part of building real capability.